Understanding temperate rainforests: researching the restoration of rare habitats at Tayvallich

An important aspect of our work at the Tayvallich Estate in Argyll is to extend the rare temperate rainforest. To help us further develop our understanding of these special habitats, we recently had two MSc students—Hannah Krull from the University of Oxford and Ben McLellan from the University of Edinburgh—working on their dissertations on different aspects of these woodlands. These projects were intended to help reveal the ecological health of different areas of woodland, how that relates to characteristics of the trees and their surrounding environment, and how detectable those characteristics are from different data sources. Ultimately, these findings will help us to restore more rainforest to higher ecological standards, on Tayvallich estate and beyond.

Blog 1

Exploring how woodland structure and environmental variables relate to temperate rainforest

Ben McLellan, University of Edinburgh

Background

As part of my MSc in Earth Observation and Geoinformation Management at the University of Edinburgh I spent 8 months working on a project about the temperate rainforest at the Tayvallich Estate managed by Highlands Rewilding. As well as the desk-based element of the work, this involved fieldwork in the woodlands to assess the rainforest fragments.

Figure 1: Some rainforest lichen pictured at Tayvallich.

The purpose of this study was to understand some of the factors relating to temperate rainforest quality which can be used to inform forest restoration and management.

Focusing on the beautiful yet fragmented temperate rainforest at Tayvallich, airborne Lidar data was used to derive woodland structure, and combined with geographic and environmental variables. Habitat quality was assessed using Plantlife’s Rapid Rainforest Assessment (RRA). The results of the analysis revealed important variables to consider in rainforest restoration, which can be used alongside the findings of previous research to develop a robust and research-driven management strategy.

Lidar Data

Lidar uses light detection and ranging technology to collect 3-D data which can be used to create accurate representations of woodland structure. The lidar data was provided to me by Highlands Rewilding and had been collected in June 2023, recording leaf-on forest structure with the Reigl VQ780i scanner. The data was stored in 3-D point clouds, which I processed using R version 4.5.0 and ArcGIS Pro version 3.3.0 to create the variables used in the analysis, as described below. The Lidar data I used covers the 5 areas of the estate highlighted in Figure 5.

Figure 2: Point cloud highlighting area of woodland, including both temperate rainforest and conifer plantation. Facing North.

Figure 3: Point cloud highlighting temperate rainforest adjacent to Taynish National Nature Reserve. Facing North.

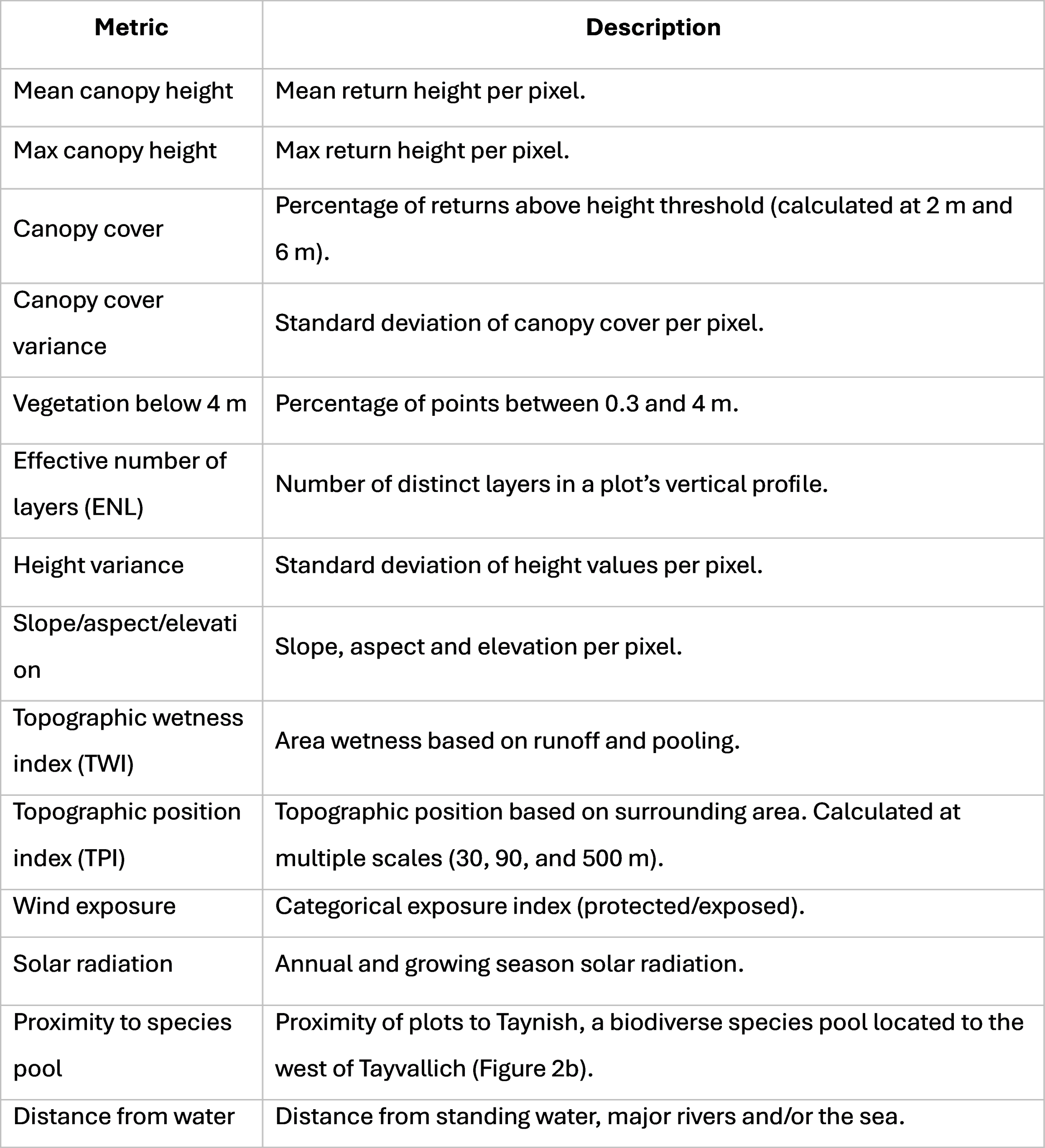

Woodland Structure and Environmental variables

From the data, I created the following metrics to represent woodland structure and the environmental/geographic variables.

Data collection

Rapid Rainforest Assessment

During the fieldwork element of the project I assessed woodland quality using Plantlife’s Rapid Rainforest Assessment (RRA)(Plantlife, 2023). The objective of the RRA is to assess the habitat suitability for the unique species of lichen and bryophytes that characterise the rainforest zone, focussing on factors such as invasive species, water features, and tree composition. The assessment provides an RRA score, which can be used to interpret and analyse habitat suitability.

Figure 4: Lobaria Pulmonaria, a distinct indicator species. (Photo credit: Plantlife, 2024c).

To incorporate current biodiversity into the analysis, ‘indicator’ species richness was recorded. Indicator species are identifiable, sensitive species of lichen and bryophytes which require the unique conditions found in temperate rainforests for survival. The species used were those found in Plantlife’s species guides (Plantlife, 2024a; Plantlife, 2024b).

Sampling

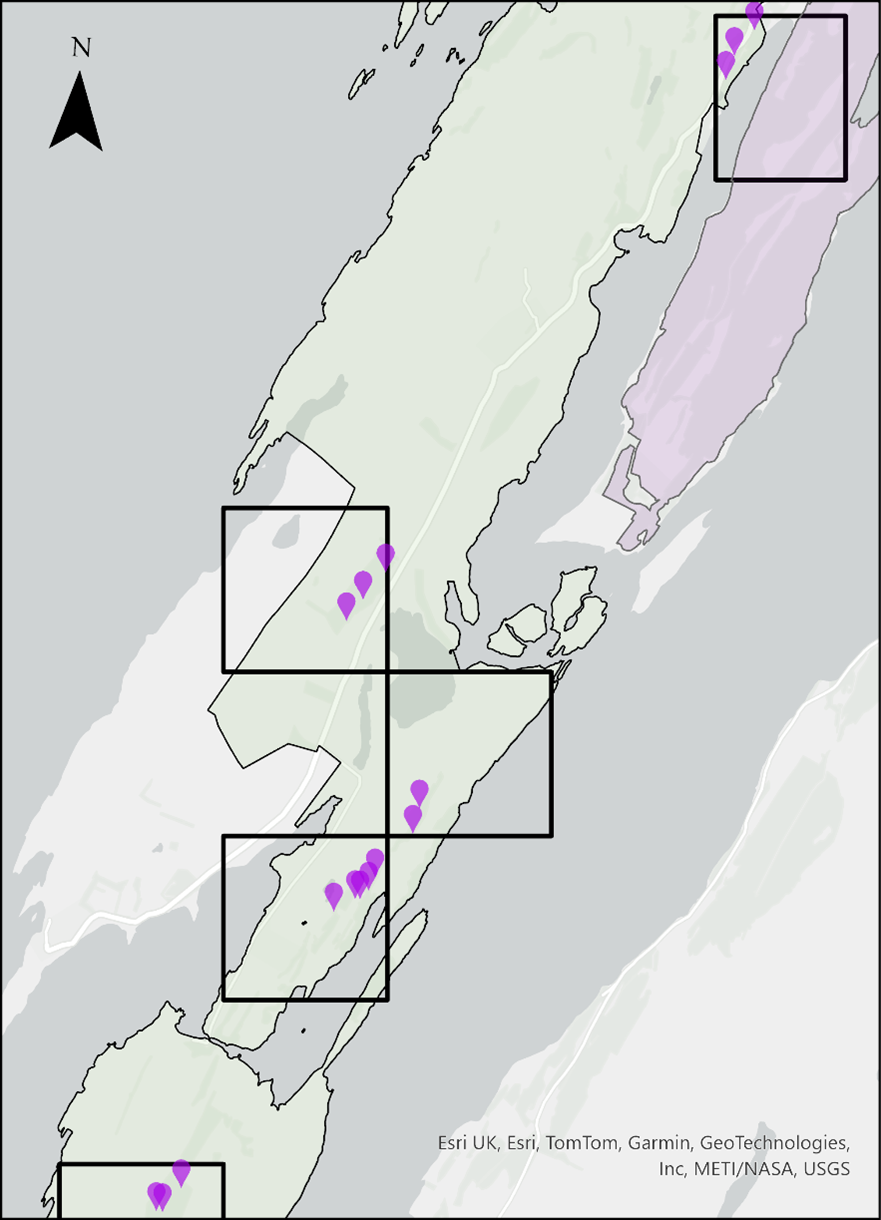

Sample sites were selected using random stratified sampling to ensure that they represented a variety of forest structures and conditions. 16 sites were sampled in June 2025, with each site being split into 4 quadrants (plots). Plots were 15 m by 15 m and the RRA was conducted in an anti-clockwise direction, starting in the northwestern plot. The resulting 64 plots were used for the analysis, and covered areas of rainforest across the whole estate.

Figure 5: The purple markers show the 16 sites sampled across Tayvallich estate, corresponding to the 64 plots used in the analysis. The black boxes show the extent of the lidar data used

Figure 6: Example survey site.

Data Analysis

To understand the link between the selected metrics and woodland quality I used Generalised Additive Models (GAMs) . GAMs are statistical models which can be used to reveal complex relationships between explanatory variables and a response variable. Being additive, GAMs highlight the effect of a variable whilst accounting for the role of other variables in the model, making them suitable for exploring ecological relationships which are often complex and multifaceted.

Findings

Results from the analysis revealed that the most important metrics relating to the quality of the rainforest were: (i) canopy cover, identifying an optimum of around 80% coverage; (ii) proximity to water, with plots closer to water having higher quality; and (iii) proximity to an existing species pool, with quality increasing with proximity. These results suggest that establishing new forests close to water and/or existing high-quality temperate rainforest, as well as aiming for around 80% canopy cover, will create ecologically rich temperate rainforests which can help Scotland meet its biodiversity commitments.

Whilst the relationships found in this study were robust, further research is required to better understand the ecological mechanisms behind them. Having said that, previous research does support these findings, whilst also identifying tree species associated with high quality rainforest (Elis and Eaton, 2021). Therefore, combining the findings of this study and those of previous research can help inform Highlands Rewilding’s planting and management strategies for the future.

References

DellaSala, D.A. (2011). Temperate and Boreal Rainforests of the World: Ecology and Conservation. Island Press, Washington, D.C.

Ellis, C.J. and Eaton, S. (2021). Microclimates Hold the Key to Spatial Forest Planning Under Climate Change: Cyanolichens in Temperate Rainforest. Global Change Biology, 27(9). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15514.

NatureScot. (2022). Scotland’s Biodiversity Strategy 2022-2045. Available at: https://www.nature.scot/scotlands-biodiversity/scottish-biodiversity-strategy/scotlands-biodiversity-strategy-2022-2045.

Plantlife (2023) Rapid Rainforest Assessment Guidance. Available at: https://www.plantlife.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Rapid-Rainforest-Assessment-GUIDANCE-1.pdf. Accessed: 06/08/2025.

Plantlife (2024a) Lichens of Scotland’s Rainforest. Guide 1 Lichens on ash, hazel, willow, rowan and old oak. Available at: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5f8efc26ea62c54078a69a6f/t/67ae4a242aa7026d5d9d108a/1739475512602/Lobarion+Lichen+Guide+1.pdf.

Plantlife (2024b) Lichens of Scotland’s Rainforest. Guide 2 Lichens on birch, alder and oak. Available at: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5f8efc26ea62c54078a69a6f/t/67ae4a5c4d54cb38161b8d84/1739475566819/Parmelion+Lichen+Guide+2.pdf.

Plantlife. (2024c) Plantlife. Tree lungwort. Available at: https://www.plantlife.org.uk/plants-and-fungi/tree-lungwort/. Accessed on: 01/04/2025.

Blog 2

Tayvallich’s Lost Rainforest Fragments Brought to Light

Hannah Krull, University of Oxford

Temperate rainforests are a hidden gem, with their concentration of high biodiversity, endemic and rare species of moss, lichens and liverworts. I recently completed a Masters project on these rainforest fragments, as part of my Biodiversity, Conservation and Management course at Oxford University, in collaboration with Highlands Rewilding. My study sought to address knowledge gaps in the distribution and structure of temperate rainforests, with particular focus on the Tayvallich Estate. Understanding how temperate rainforest distribution and structure varies across the landscape, and where healthy, connected ecosystems still exist, provides a basis for restoration projects to reconnect and expand remnant fragments.

Figure 10: Native and non-native trees growing in the rainforest zone, Tayvallich

To achieve high resolution data collection, remote sensing methods using drone flights of light detection and ranging, or LiDAR, sensors were chosen to map rainforest fragments, along with on-the-ground field data to accurately identify tree species and canopy structure. Drone-based LiDAR data was collected in March 2023 by a team from Oxford University, and fieldwork on three rainforest survey plots was completed in June 2024 by a team of rangers and scientists at Highlands Rewilding. Data was used to estimate and compare the structural complexity, above ground biomass and carbon storage found in the native forest fragments across the estate.

In the north, more structurally complex native rainforest fragments were clustered with larger tree counts and heights suggesting greater tree maturity and lower disturbance. These species-rich rainforest fragments consist of native oak, birch and hazel forest. Moving southwards, Sitka spruce plantations exist in the centre of Tayvallich estate, producing fast-growing non-native forests at an average height of over 18 metres. In southern Tayvallich, low tree counts, densities and heights across a large area, with little canopy variation, indicated the greatest disturbance regime, with young trees in the early stages of succession. The south of Tayvallich may have seen greater agricultural conversion than the north, although low tree heights are also associated with wind in this exposed part of the Scottish west coast.

Figure 11: The locations of native woodland and woodland census plots on the Tayvallich peninsula

Figure 12: The height distributions of trees in each of the three plots surveyed. Locations are shown in Figure 11

The greater tree coverage and structural diversity in northern Tayvallich indicates greater biomass accumulation, as well as suggesting improved ecosystem functioning and resilience. Nevertheless, much of the biomass is held in non-native plantation forest with low structural diversity, implying a trade-off between growth rates and growth forms.

Rainforest regeneration can be facilitated by creating habitat corridors using natural regeneration supplemented by planting native species. In Tayvallich this could comprise new forest areas running north-south through the estate, joining fragments found at either end. Fostering connectivity across a landscape is key to creating habitat corridors for species movement and colonisation using both managed and natural regeneration.

Adaptive management plans are needed to respond to the threats posed by climate change, invasive species and disease, which will require active management and long-term monitoring. The insights work of this kind provides into the most structurally complex areas of temperate rainforest will support such management. More widely, understanding the distribution and characteristics of temperate rainforest in Britain is crucial to protecting threatened native species and evaluating how their ecological functions can be utilized to increase ecosystem services. Tayvallich forms a small fragment of a larger network of temperate rainforest which must be reconnected to develop habitat corridors that mitigate the rising effects of climate change, providing a rainforest refuge for endemic species.