Fences in the landscape

Daniel Holm, Head Ranger at Bunloit

Fences stretch tendrils of human influence out into the natural world. Used to contain livestock, delineate march boundaries between estates, and protect newly planted woodland from deer pressure. These three land uses cover the vast majority of Scotland's land area, so fences can be found almost anywhere. They are so ubiquitous in the landscape that their presence is often not given a second thought.

Fences certainly have their place in various land uses and are very effective in their primary purpose, to keep things on one side or another. This can be extremely useful in farming and forestry. Still, fences can also act as a marker for those who are out roaming the land, giving warning that they are potentially crossing over into an area of different land use and making them aware of any risks that might stem from these differing operations, be that livestock, forestry, stalking or similar.

Old fence posts at Bunloit

However, many fences in the landscape no longer serve their original purpose, whether because a newly planted forest is past the stage at which it needs protection, estate boundaries have changed, or farming methods have changed. Often, these fences are left where they are rather than being removed; since it is labour-intensive to remove them, there is no financial incentive to remove them, and all of the old fencing must be disposed of.

Redundant fences pose a barrier to free movement of wildlife and can be a danger to some. Deer can become tangled in the top wires of a fence as they try to jump them and die a long, slow death tangled in the wire. They also break the landscape up into smaller parcels rather than it being one continuous open space as it should be naturally.

In a country where we have the right to roam, these unassuming human structures do a lot to take that right away. When walking in a landscape with a fence, subconsciously, the message is, "You can not go that way", although you could climb it and risk damaging the fence or yourself and your clothing on barbed wire. If you remove the fence, immediately the landscape opens up for you to explore freely in whichever direction you want.

So, our policy at our Bunloit estate has been to remove fences that no longer serve a purpose. Which turns out to be a lot of fencing. Where it has been possible to remove old wire netting in good condition, we have given it away to local farmers for reuse. The wire and mesh in poor condition are collected and sent for recycling. Most old posts are currently being recycled into tree guards in the forest garden. Those past the point of being reused are also gathered in and sent to be recycled.

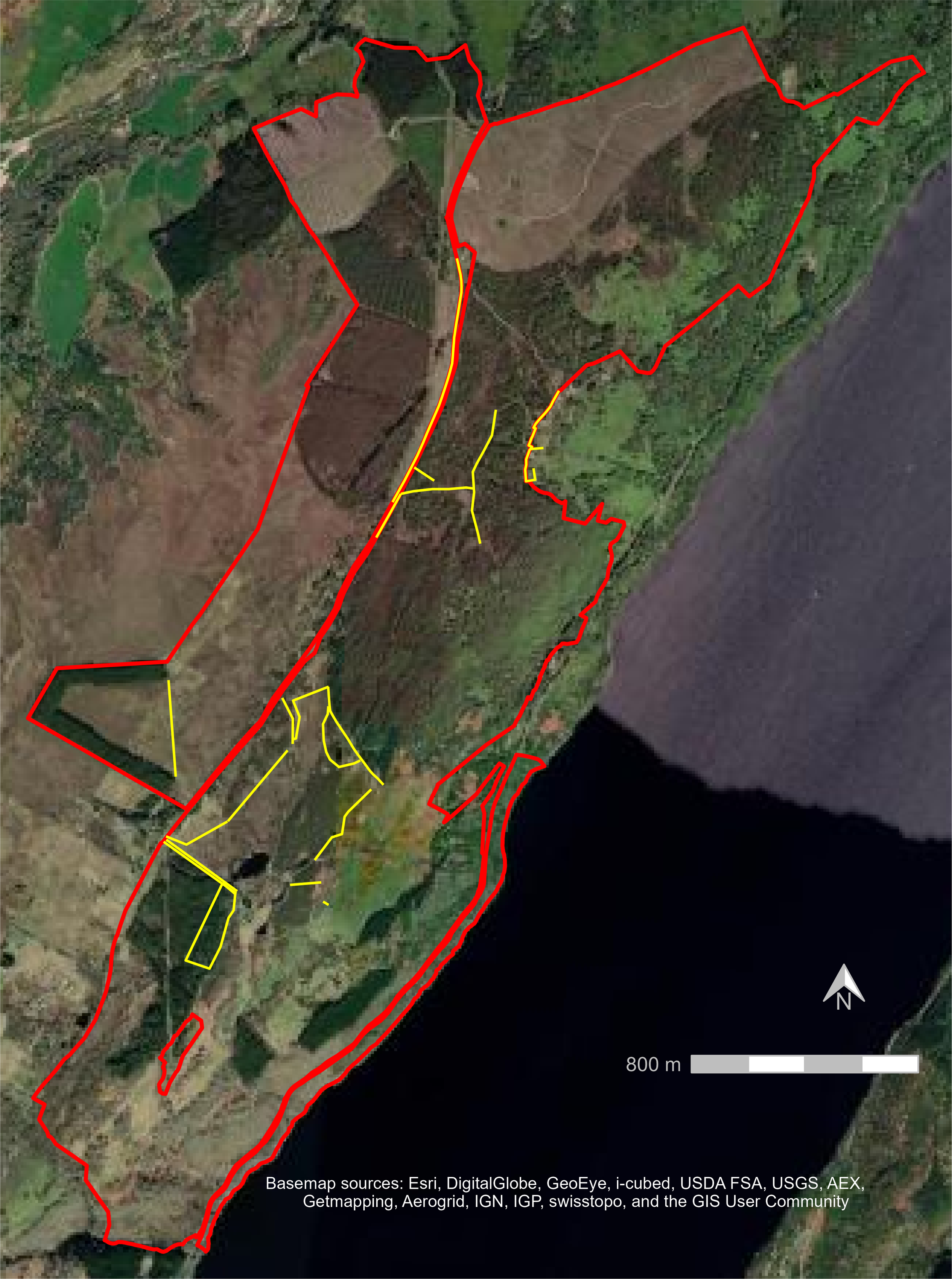

Left: Bunloit site. Red lines mark the estate boundary. Yellow lines mark removed fences.

Right: Daniel, Head Ranger, removing fences at Bunloit.

There are sometimes posts, usually strainer posts, which refuse to be removed from the ground. Instead of struggling to remove these or cutting them down with a chainsaw and risking blunting the saw on an unseen staple, we leave them where they are. Individual posts like this can benefit biodiversity, becoming perches for birds of prey and other birds, and providing a micro habitat for lichens, fungi, plants and insects. They provide what is essentially a standing deadwood habitat, which can support various species that otherwise would not survive in this particular location because the conditions on the ground are not suitable for them.

Top: old fence posts. Bottom: the reuse of fences as tree guards for Bunloit’s food forest.